You Know It's Fake News; It Still Affects What You Believe

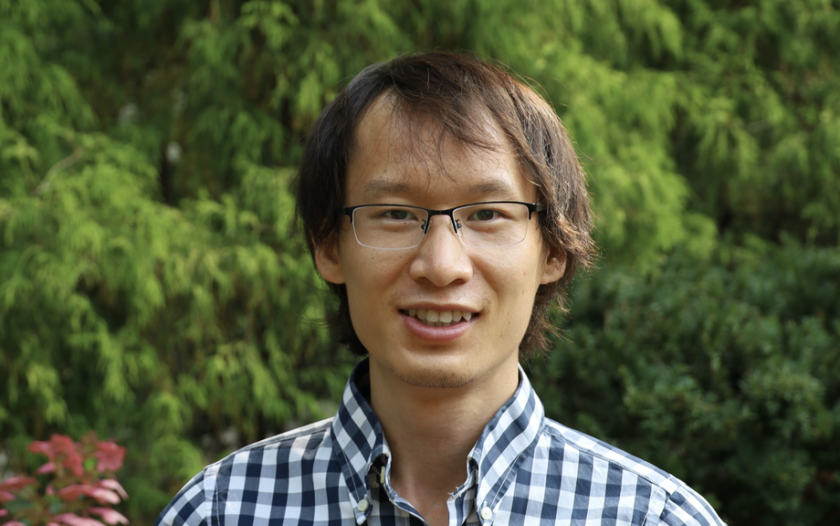

Editor's note: Max Hui Bai is one of Stanford Impact Lab's first four postdoctoral fellows. Through the fellowship, he is working with Stanford's Politics and Social Change Lab to understand how identities and ideologies between groups of people affect political polarization. He recently shared insights from his research with the Association for Psychological Science's annual convention in Chicago that drew 2,500 attendees from around the world to focus on how psychological science can build a better, more just society.

Q. What does your research focus on?

Much psychological research on how we can combat misinformation focuses on improving citizens’ ability to recognize misinformation as false. My research addresses whether misinformation we already recognize as misinformation can still change our beliefs and attitudes. This is important because if we are affected by misinformation we already know is false, then the media’s repeated debunking of misinformation might be ineffective, or worse, backfire.

Q. What have you found so far?

I found in five experiments that Americans’ beliefs and behavioral intentions were still changed by reading something they knew was made-up and created political polarization where there was none initially. The impacts of exposure to what people know is false is hard to get rid of and can last for days. I shared early thoughts on the research in a Twitter thread last September. The full paper, with updates since then, is under review.

Q. Who is interested in the research and why?

The point that just helping people recognize misinformation as false may not be sufficient to reduce polarization seems to be resonating with people. Those who spoke to me at the Association for Psychological Science conference really got it and were curious about what else we can do, perhaps structurally, to reduce misinformation's presence in the first place.

It's also really important for policymakers and members of the media to know about this research so it can inform what they do in response to misinformation and to help prevent misinformation from being produced and circulated in the first place.

Q. What is the Stanford Impact Labs postdoctoral fellowship helping you do differently?

Within academia, people are still mostly evaluated based on their theoretical contributions to the field. Stanford Impact Labs' postdoctoral fellowship really helps me think about what type of research questions I should ask and study that others can use. It has also been very helpful to me to write about my research in a way that connects to the real world, communicating and engaging audiences beyond academia who can shape the research and use it in their own work. I am very grateful to my advisor Robb Willer here at the Politics and Social Change Lab who has incredible insights here.

Q. Why do you think this work is resonating right now?

Misinformation has been exploding and people’s exposure to it has, in the past year alone, contributed to a public health crisis and a political insurrection. Understanding how best to address the issue has never been more critical to a functional democracy we all live in today.

Q. What’s surprised you about the work so far?

I was surprised how hard it is to get rid of the effect of exposure to misinformation even when we already know that information is false. In the experiments, I tried telling people to be deliberative or just provided them with real information. Their beliefs were still affected by the misinformation they already knew was false.

I was also somewhat surprised that misinformation—even when known to be false—can create political polarization where there is none. In one study, I gave participants misinformation that Democrats and Republicans disagree on something, which participants understood was not real. Both Democrat and Republican participants later on adopted the position described in the misinformation that, again, they knew was not real! This was shocking to me.

From what I can tell, it means it would be easy for someone with ulterior motives to create political polarization. If one wants to polarize partisans’ stance on a new social issue, they could just post something on social media about how Democrats and Republicans disagree on it. It may be flagged by the platform as false, but if only a few partisans pick it up and end up believing it, their beliefs will create a partisan norm that is real, and this norm may ultimately cascade into a bigger and intractable polarization.

Q. What's next?

The paper is under review now. I’m interested to see what kind of interest and ideas it might generate and hope people will reach out to me at or @baixx062 on Twitter. In the next few months, however, I'm going to be shifting some attention to other projects about race and politics. One project I am particularly excited about is how we perceive others through their beliefs. For example, I found people perceive liberals as more likely to be Black and to have a darker skin color, and I am looking forward to learning what people think about it.