Expanding Access to Reproductive Health Technologies

Reproductive autonomy is the power to determine whether and when to have children. It often depends on where people live, how much money they have, and their cultural or ethnic landscape.

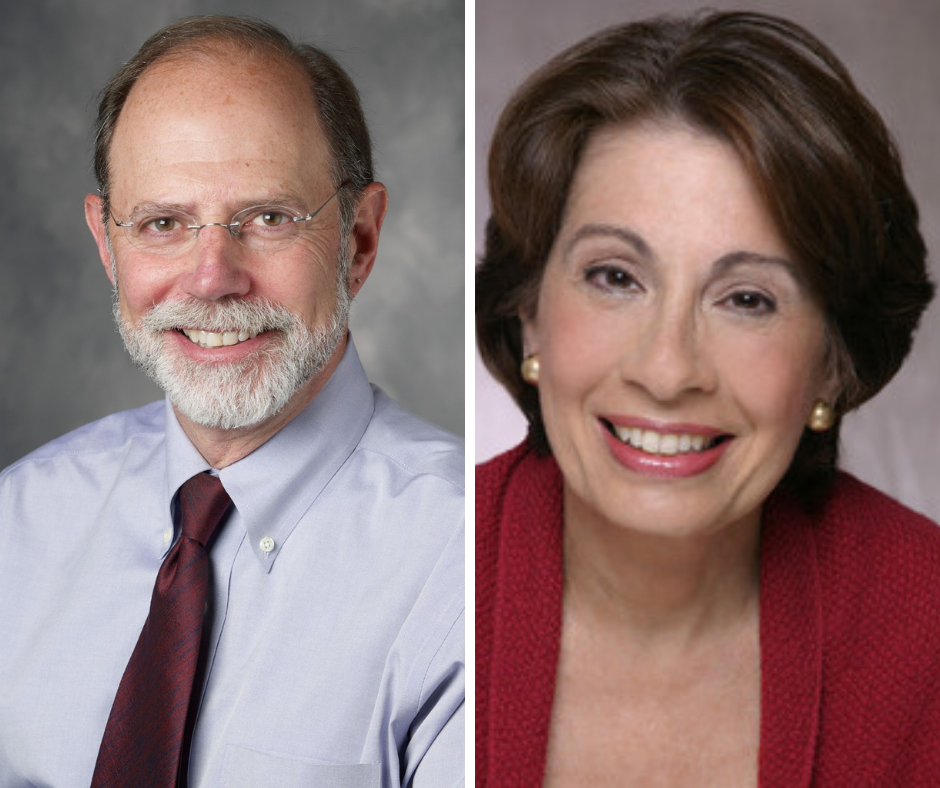

Gynuity Health Projects is a global research and technical assistance organization that works to ensure all people have access to reproductive health technologies. Beverly Winikoff, a physician and public health scientist and founder of Gynuity Health Projects, and Paul Blumenthal, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University, describe their team’s efforts to create new ways for individuals to use reproductive health services where and when they need them. Their team is one of six to receive start-up funding from Stanford Impact Labs for 2021-2023.

Q. What is the social problem you are working on?

PAUL BLUMENTHAL (Stanford): Our research team is working to ensure reproductive autonomy: the power to determine whether and when to bear children. Barriers to reproductive autonomy, including access to abortion, intersect with a number of other social issues. Access depends, in great measure, on where people live, how much money they have, and what ethnic, cultural, and religious communities they inhabit.

Much of the "know-how" we need to advance reproductive autonomy is available now. However, the technology has outpaced the knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of providers and regulators, as well as those of the general public and potential users. Our goal is to ensure underutilized technologies, like medication abortion, are used according to best practices and are available to those who want them. What could matter more than ensuring all people can make choices about their bodies?

Q. What will the start-up lab funding and team approach help you do?

BEVERLY WINIKOFF (Gynuity Health Projects): Collaboration with a range of partners is integral to Gynuity’s model of work and has been vital to our eighteen years of research and policy change. We engage with ministries of health, community-based organizations, hospitals, clinics, hospital networks, social marketing organizations, pharmaceutical entities, global norm-setting bodies, regulatory bodies, research organizations and independent providers and advocates.

The start-up lab funding and team approach is exciting and different, because the Stanford team and Gynuity were encouraged to be collaborative and equal partners in our proposal. Funding mechanisms can often be a barrier to partnership due to the rules and policies imposed by funders. However, the Stanford Impact Labs’ approach creates the possibility of partnership without hurdles.

PAUL BLUMENTHAL (Stanford): Gynuity operates both domestically and internationally and within and outside academia. They have a different, often more programmatic perspective than the Stanford team. Merging our strengths and diverse experience and viewpoints will generate better evidence and approaches that are likely to benefit more people.

This start-up lab opportunity also let our Stanford-based research team fully partner with Gynuity in developing the proposal and generating ideas for our work together. This is unique and unlike many investigator-initiated university research programs where project collaborators are most often involved only in “downstream” activities such as participant recruitment or interpretation of results. It means we have, and will continue to have, equal effort and buy-in on the project. It will improve both our science and our impact.

Q. What are you most excited about with this work?

BEVERLY WINIKOFF (Gynuity Health Projects): For us, the purpose of good science is to create reliable knowledge that will be used to improve social well-being. We aspire to make safe, high quality abortion services more accessible to those who need them.

Our work can make abortion care less constrained, more available, and more mainstream, similar to other areas of healthcare. We are advancing and advocating for innovations that the general public and experts in the field said “couldn’t be done.” We are realizing the potential of technologies that can be used in all settings—low- and high-resource, domestically and internationally. Most of all, we are excited that this is only the beginning of a potential revolution in self-care affecting a fraught area of medicine.